Scientists have built a miniature female reproductive tract using human tissue. They want to use it to screen new drugs for women.

The ultimate goal is to use stem cells to create personalized models of a patient’s reproductive system.

“This will help us develop individualized treatments and see how females may metabolize drugs differently from males,” says lead investigator Teresa Woodruff, a reproductive scientist and director of the Women’s Health Research Institute at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

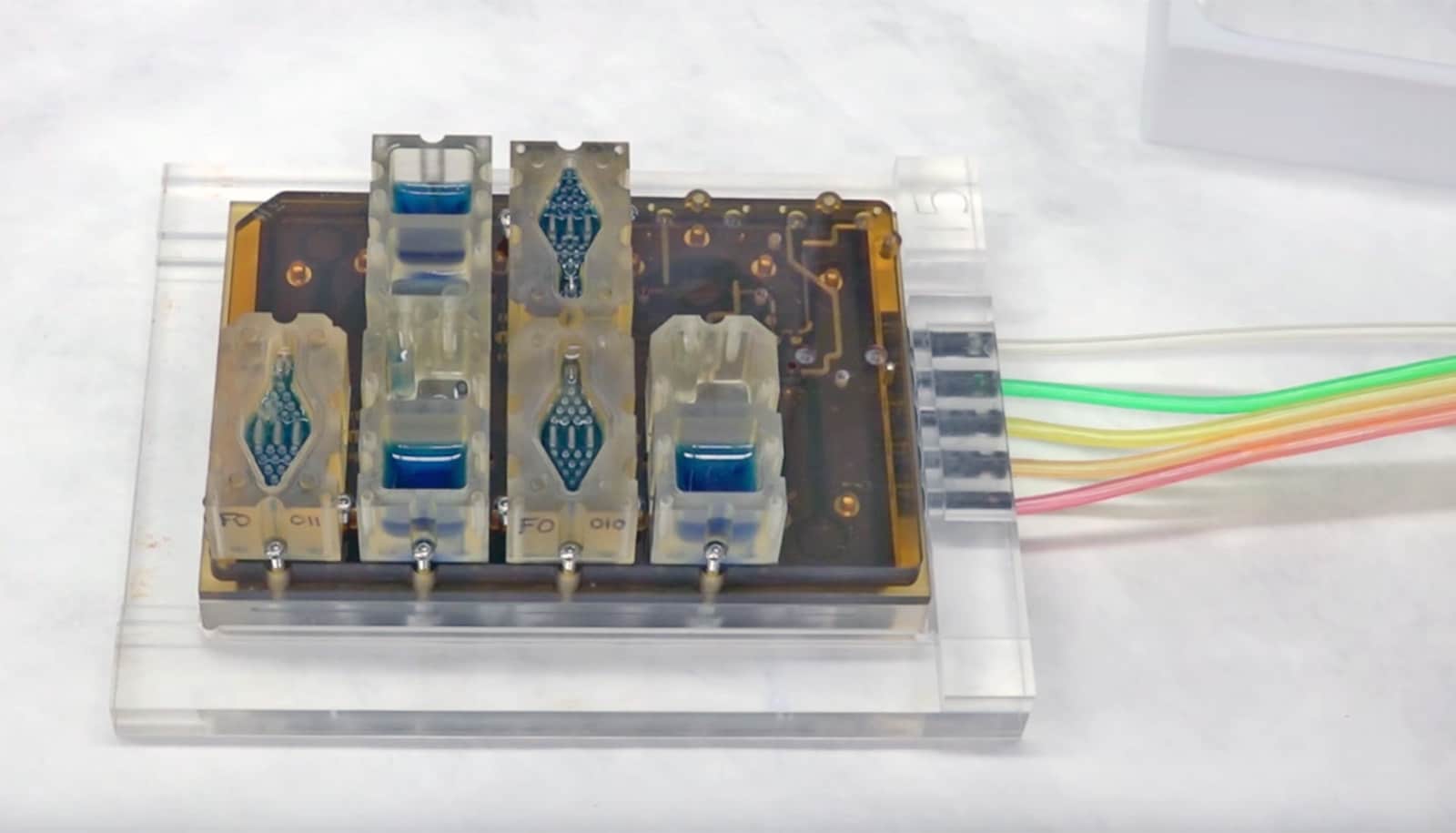

The technology is called EVATAR. It contains 3D models of ovaries, fallopian tubes, the uterus, cervix, vagina, and liver with special fluid pumping through all of them that performs the function of blood.

EVATAR can test drug safety and effectiveness. It can also help scientists understand diseases such as endometriosis, fibroids (which affect up to 80 percent of women), cancer, and infertility.

“This is nothing short of a revolutionary technology,” says Woodruff, who describes the work in a paper published in Nature Communications.

Your body on a chip

The organ models are able to communicate with each other via secreted substances, including hormones, to closely resemble how they all work together in the body.

Woodruff is working on the project with other scientists at Northwestern, the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), and Draper Laboratory, Inc.

“It’s the ultimate personalized medicine, a model of your body for testing drugs.”

The project is part of a larger National Institutes of Health effort to create “a body on a chip.”

“If I had your stem cells and created a heart, liver, lung, and an ovary, I could test 10 different drugs at 10 different doses on you and say, ‘Here’s the drug that will help your Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s or diabetes,'” Woodruff says. “It’s the ultimate personalized medicine, a model of your body for testing drugs.”

How EVATAR works

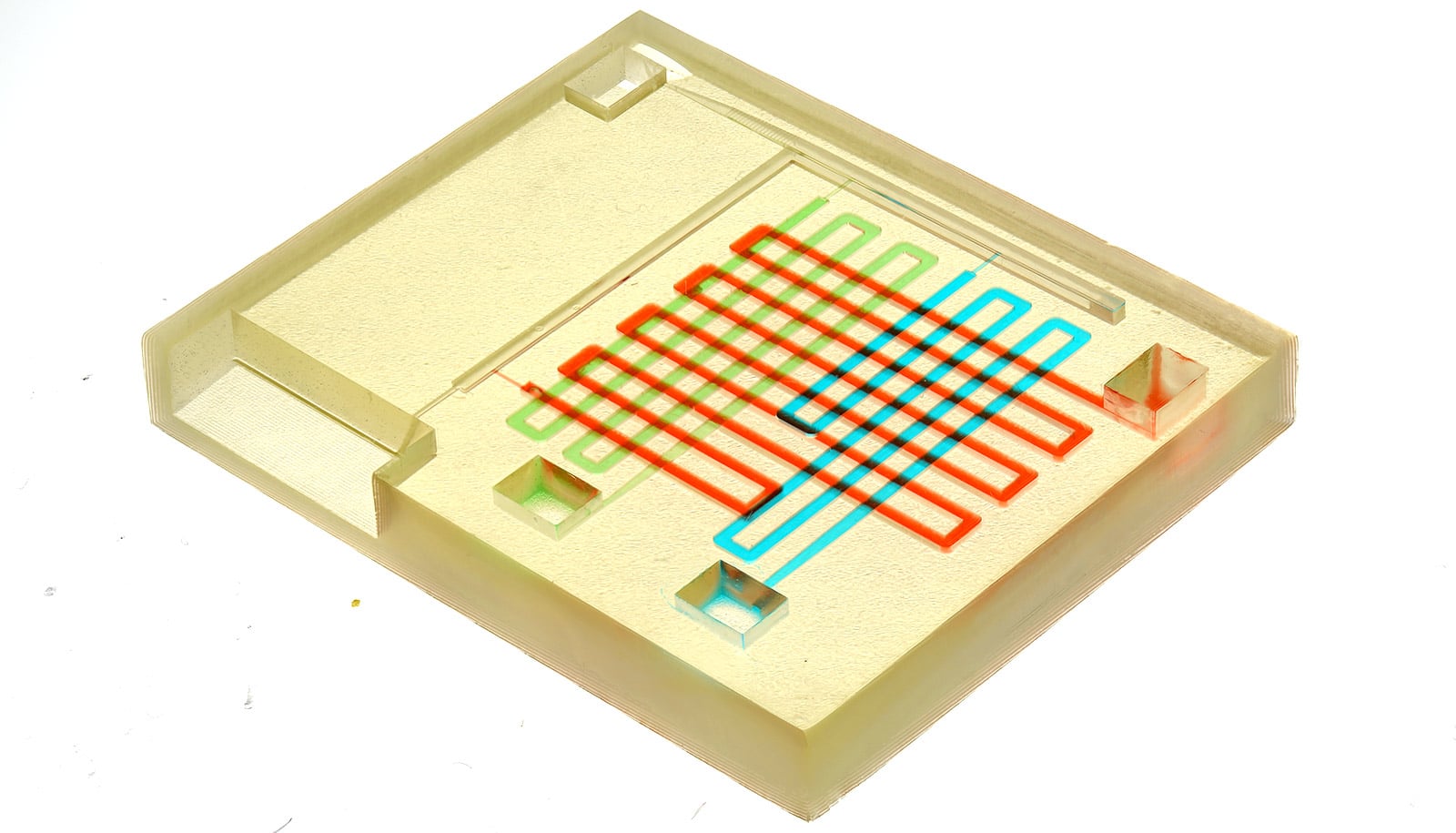

The EVATAR technology is revolutionary because the reproductive tract creates a dynamic culture in which organs communicate with each other rather than having static cells sit in a flat plastic dish.

“This mimics what actually happens in the body,” Woodruff said. “In 10 years, this technology, called microfluidics, will be the prevailing technology for biological research.”

The microfluidic device is the size of a bento box and has a series of cables and pumps that cause media (simulated blood) to flow between wells.

‘Kidney on a chip’ could lead to precision drug dosing

The technology also will open doors into the causes of endometriosis, fibroids, and some cancers.

“All of these diseases are hormonally driven, and we really don’t know how to treat them except for surgery,” says Joanna Burdette of UIC who developed the fallopian tubes. “This system will enable us to study what causes these diseases and how to treat them.”

“The systems are tremendous for the study of cancer, which often is studied as isolated cells rather than system-wide cells. This is going to change the way we study cancer,” Burdette adds.

It has circulating ‘blood’

The system also will allow scientists to test millions of compounds in the environment and new pharmaceuticals to understand how they affect the reproductive system and many other organs in the body.

“This technology will help us look at drug testing and drug discovery in a brand new way,” Woodruff says.

They system should be able to identify effective drugs and ineffective ones early in the drug discovery process, allowing developers to refocus resources on the strong candidates earlier and end unproductive research earlier, minimizing costs, says Jeffrey T. Borenstein, a biomedical engineer at Draper.

The new technology works largely because the scientists developed a universal medium that acts in the same way as blood and circulates between each of the organ systems.

“One of the reasons this technology has not advanced in the past is no one had solved the universal media problem,” Woodruff says. “We reasoned that organs in the body are in one medium—the blood—so we created a simple version of the blood and allowed the tissues to communicate via the medium.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the work.

Source: Northwestern University