An ancient monitor lizard with a fourth eye may signal a new wrinkle in eyesight’s evolution in vertebrates.

“This tells us how easy it is, in terms of evolution, to self-assemble a complex organ under certain circumstances,” says Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, a paleontologist at Yale University and coauthor of a new study that appears in Current Biology.

“Eyes are classically conceived of as these remarkably complex structures. In fact, the developing brain is just waiting to make eyes given the right signals,” he says.

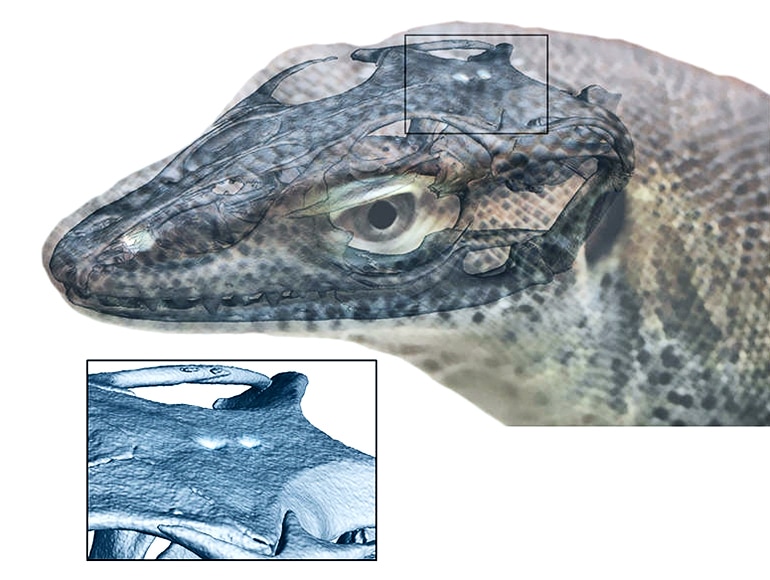

In the study, researchers present evidence that pineal and parapineal eyes, located on the top of the head, were present simultaneously in Saniwa ensidens, an extinct monitor lizard that lived nearly 50 million years ago.

The pineal organ, which is sometimes called the “third eye” when it has a lens and retina, exists in a number of lower vertebrates such as fish and frogs, and was widespread in primitive vertebrates. Some scientists have suggested that most of the higher vertebrates—other than lizards—dispensed with the third eye independently, while other scientists have suggested that the lizard third eye develops from a different organ, the parapineal.

“By discovering a four-eyed lizard, in which both the pineal and parapineal organs formed an eye on the top of the head, we could show that the lizard third eye really is different from the third eye of other vertebrates,” says lead author Krister Smith, a former Yale graduate student now at the Senckenberg Research Institute.

Using CT-scanning technology, the researchers studied the structures of small, fragmentary fossils of Saniwa ensidens collected in the 1870s. This technique allowed the researchers to clarify that the pineal and parapineal eyes were not a pair of organs.

“It’s important to recognize that there’s nothing mystical about the pineal and parapineal organs,” Smith says. “They can sense light and play a role in the endocrine system. However, some of the abilities conferred by the pineal are really quite extraordinary. For instance, some lower vertebrates can sense the polarization of light with the third eye and use this to orient themselves geographically.”

How ‘true frogs’ buck assumptions about evolution

Smith and Bhullar say the findings illustrate how little is known about the evolutionary timing of the so-called “lizard shift,” the appearance of the third eye in lizards. Further study is necessary, they say, in order to fully understand the development of eyesight in a variety of vertebrates.

“The eye is fundamentally a part of the brain,” Bhullar says. “The way an eye forms is that the developing brain comes in contact with part of the embryonic skin. This contact begins a self-sustaining molecular cascade that concludes in the formation of an eye with lens and retina.”

Other researchers from the Senckenberg Research Institute are coauthors of the study. Grants from the National Science Foundation and the German Science Foundation funded the research in part.

Source: Yale University