The way “beams” in human bone material handle a lifetime’s worth of wear and tear could lead to longer lasting 3D-printed lightweight materials, researchers report.

When researchers mimicked this beam and made it about 30% thicker, they could make an artificial material last up to 100 times longer.

“Bone is a building. It has these columns that carry most of the load and beams connecting the columns. We can learn from these materials to create more robust 3D-printed materials for buildings and other structures,” says Pablo Zavattieri, a professor in the Lyles School of Civil Engineering at Purdue University.

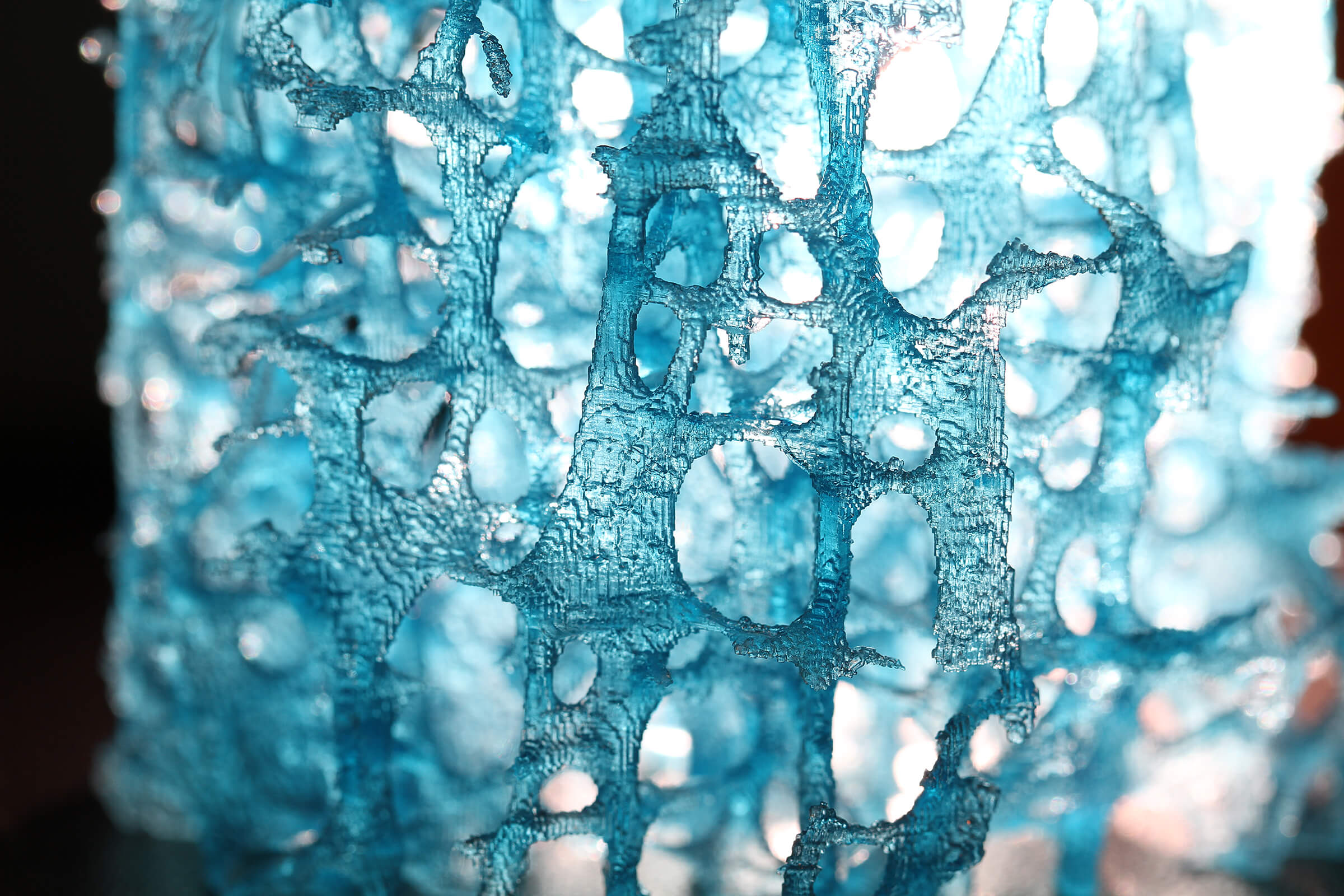

Bones get their durability from a spongy structure called trabeculae, which is a network of interconnected vertical plate-like struts and horizontal rod-like struts acting as columns and beams. The denser the trabeculae, the more resilient the bone for everyday activities. But disease and age affect this density.

The researchers found that even though the vertical struts contribute to a bone’s stiffness and strength, it is actually the seemingly insignificant horizontal struts that increase the fatigue life of bone.

Christopher Hernandez’s group at Cornell University had suspected that horizontal strut structures were important for bone durability, contrary to commonly held beliefs in the field about trabeculae.

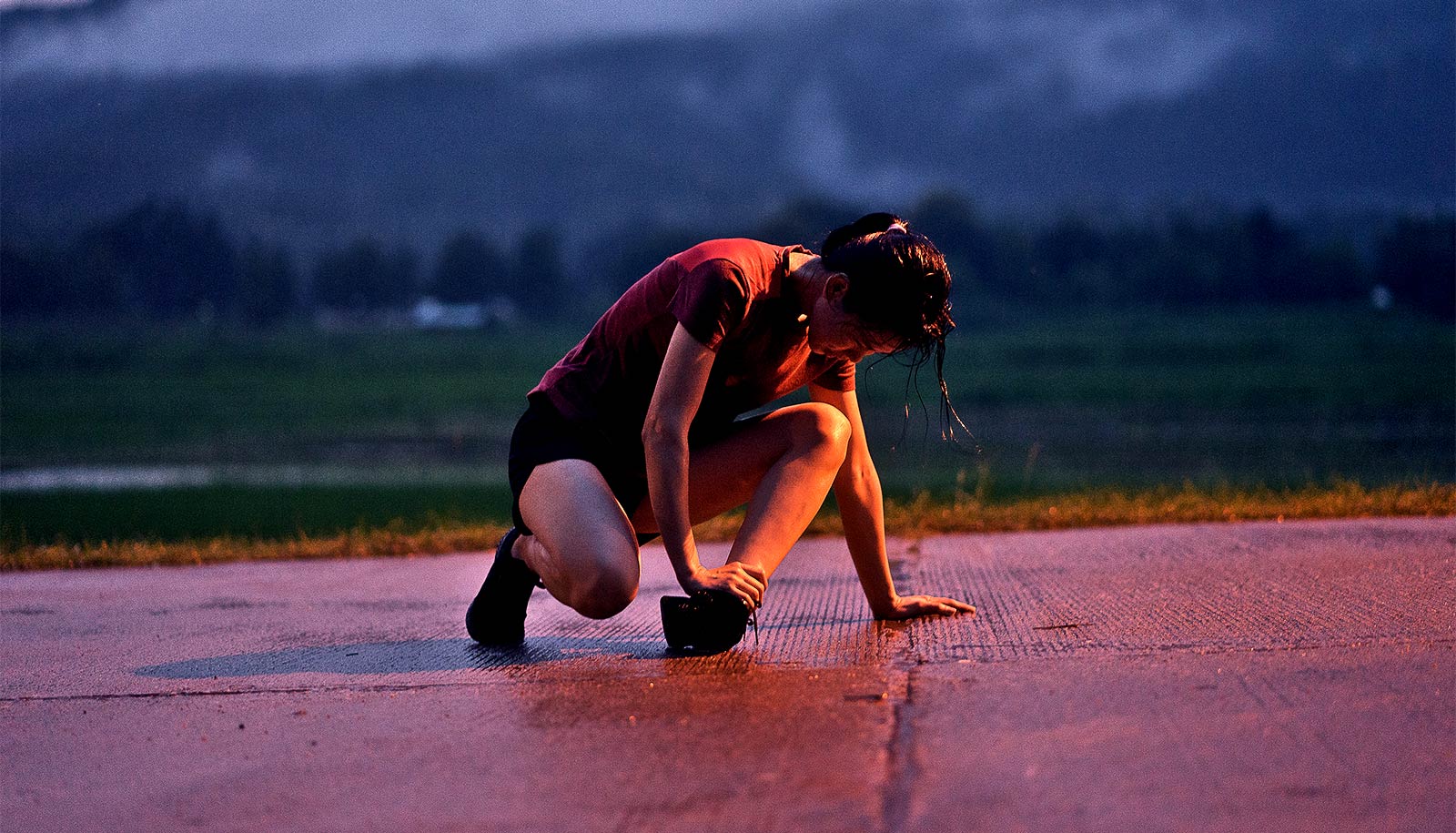

“When people age, they lose these horizontal struts first, increasing the likelihood that the bone will break from multiple cyclic loads,” says Hernandez, a professor of mechanical, aerospace, and biomedical engineering.

Studying these structures further could inform better ways to treat patients suffering from osteoporosis.

Meanwhile, 3D-printed houses and office spaces are making their way into the construction industry. While much faster and cheaper to produce than their traditional counterparts, even printed layers of cement would need to be strong enough to handle natural disasters—at least as well as today’s homes.

That problem could be solved by carefully redesigning the internal structure, or “architecture,” of the cement itself. Zavattieri’s lab has been developing architected materials inspired by nature, enhancing their properties and making them more functional.

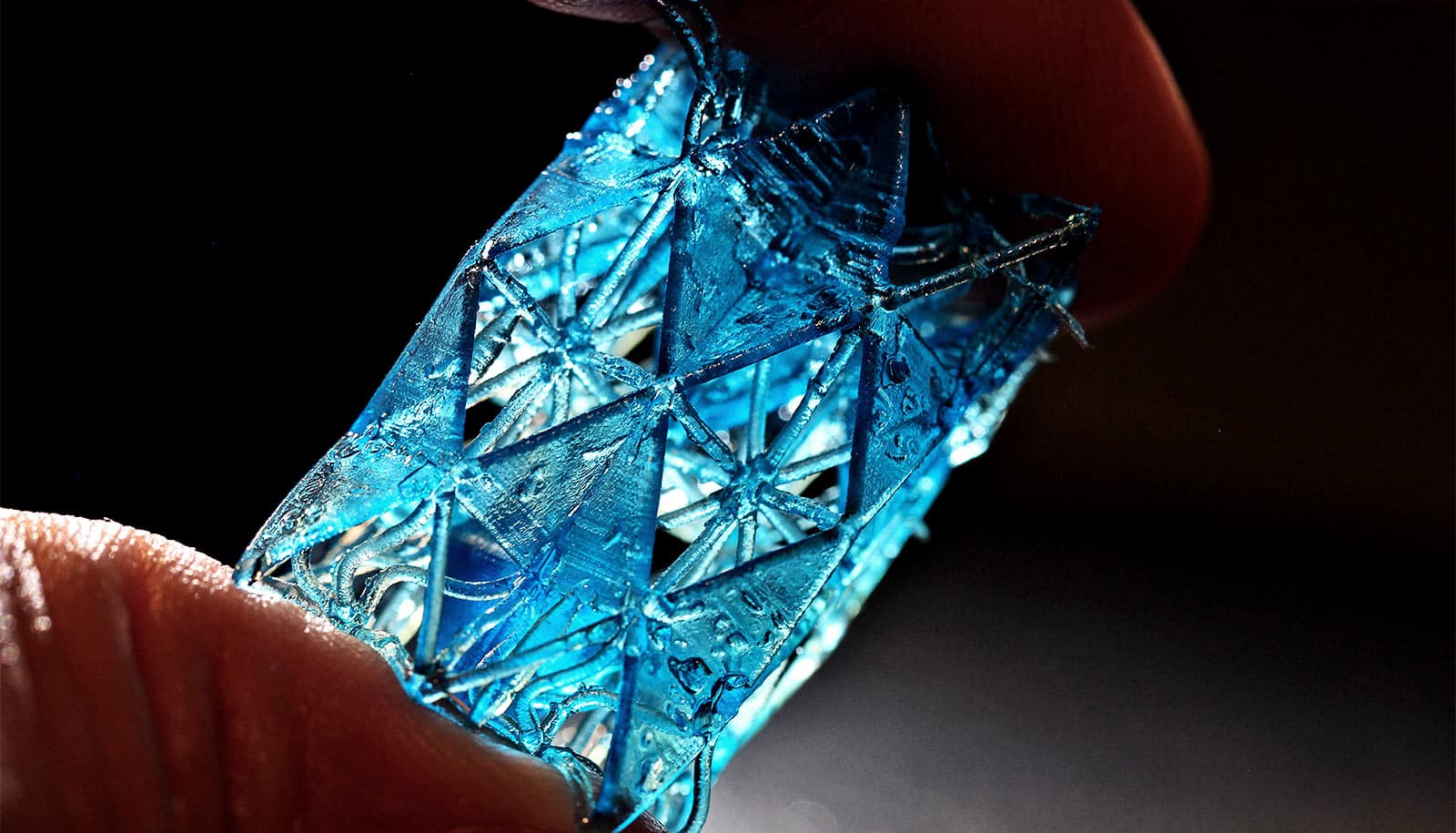

As part of an ongoing effort to incorporate nature’s best strength tactics into these materials, Zavattieri’s lab contributed to mechanical analysis simulations determining if horizontal struts might play a larger role in human bone than previously thought. They then designed 3D-printed polymers with architectures similar to trabeculae.

The simulations revealed that the horizontal struts were critical for extending the fatigue life of bone.

“When we ran simulations of the bone microstructure under cyclic loading, we were able to see that the strains would get concentrated in these horizontal struts, and by increasing the thickness of these horizontal struts, we were able to mitigate some of the observed strains,” says coauthor Adwait Trikanad, a civil engineering PhD student.

Applying loads to the bone-inspired 3D-printed polymers confirmed this finding. The thicker the horizontal struts, the longer the polymer would last as it took on load.

Because thickening the struts did not significantly increase the mass of the polymer, the researchers believe this design would be useful for creating more resilient lightweight materials.

“When something is lightweight, we can use less of it,” Zavattieri says. “To create a stronger material without making it heavier would mean 3D-printed structures could be built in place and then transported. These insights on human bone could be an enabler for bringing more architected materials into the construction industry.”

The study appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Additional coauthors came from Cornell and Case Western Reserve University.

The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and a National Science Foundation CAREER award supported the work.

Source: Purdue University