Researchers have taken advantage of a common defect of the least-expensive kind of 3D printer to produce flat plastic items that, when heated, fold themselves into predetermined shapes, such as a rose, a boat, and even a bunny.

The objects are a first step toward products such as flat-pack furniture that assume their final shapes with the help of a heat gun, says Lining Yao, assistant professor in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute and director of the Morphing Matter Lab at Carnegie Mellon University.

The technology could also lead to emergency shelters that could ship flat and fold into shape under the warmth of the sun.

Self-folding materials are quicker and cheaper to produce than solid 3D objects, making it possible to replace noncritical parts or produce prototypes using structures that approximate the solid objects. The materials could be useful for creating molds for boat hulls and other fiberglass products inexpensively.

Other researchers have explored self-folding materials, but have typically used exotic materials or depended on sophisticated processing techniques not widely available.

Yao and colleagues created their self-folding structures by using the least expensive type of 3D printer—an FDM printer—and by taking advantage of warpage, a common problem with them.

“We wanted to see how self-assembly could be made more democratic—accessible to many users,” Yao says.

FDM printers work by laying down a continuous filament of melted thermoplastic. The materials contain residual stress and, as the material cools and the stress is relieved, the thermoplastic tends to contract. This can result in warped edges and surfaces.

“People hate warpage,” Yao says. “But we’ve taken this disadvantage and turned it to our advantage.”

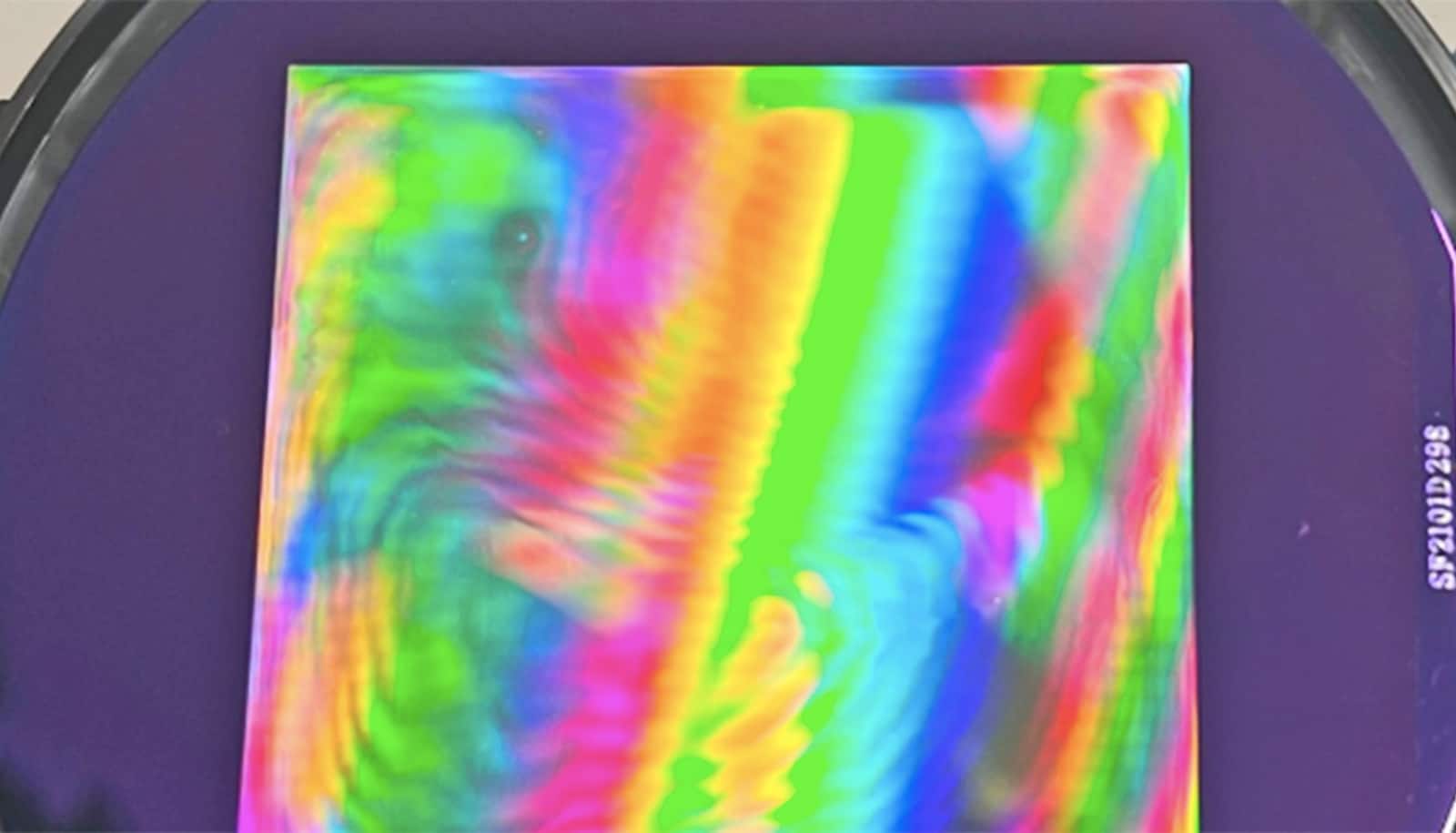

To create self-folding objects, the researchers precisely control the process by varying the speed at which the printer deposits thermoplastic material and by combining warp-prone materials with rubber-like materials that resist contracture.

This 3D printing method makes a better nose

The objects emerge from the 3D printer as flat, hard plastic. When the plastic is placed in water hot enough to turn it soft and rubbery—but not hot enough to melt it—the folding process is triggered.

Though they used a 3D printer with standard hardware, the researchers replaced the machine’s open source software with their own code that automatically calculates the print speed and patterns necessary to achieve particular folding angles.

“The software is based on new curve-folding theory representing banding motions of curved area. The software based on this theory can compile any arbitrary 3D mesh shape to an associated thermoplastic sheet in a few seconds without human intervention,” says Byoungkwon An, a research affiliate in HCII.

“It’s hard to imagine this being done manually,” Yao says.

Though these early examples are at a desktop scale, making larger self-folding objects appears feasible.

“We believe the general algorithm and existing material systems should enable us to eventually make large, strong self-folding objects, such as chairs, boats, or even satellites,” says Jianzhe Gu, HCII research intern.

Yao will present her research, called Thermorph, at the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2018).

5 ways 3D printing could totally change medicine

An, Gu, and Ye Tao are lead authors of the paper. Other coauthors are from Carnegie Mellon, Zhejiang University, Syracuse University, the University of Aizu, and TU Wien.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University