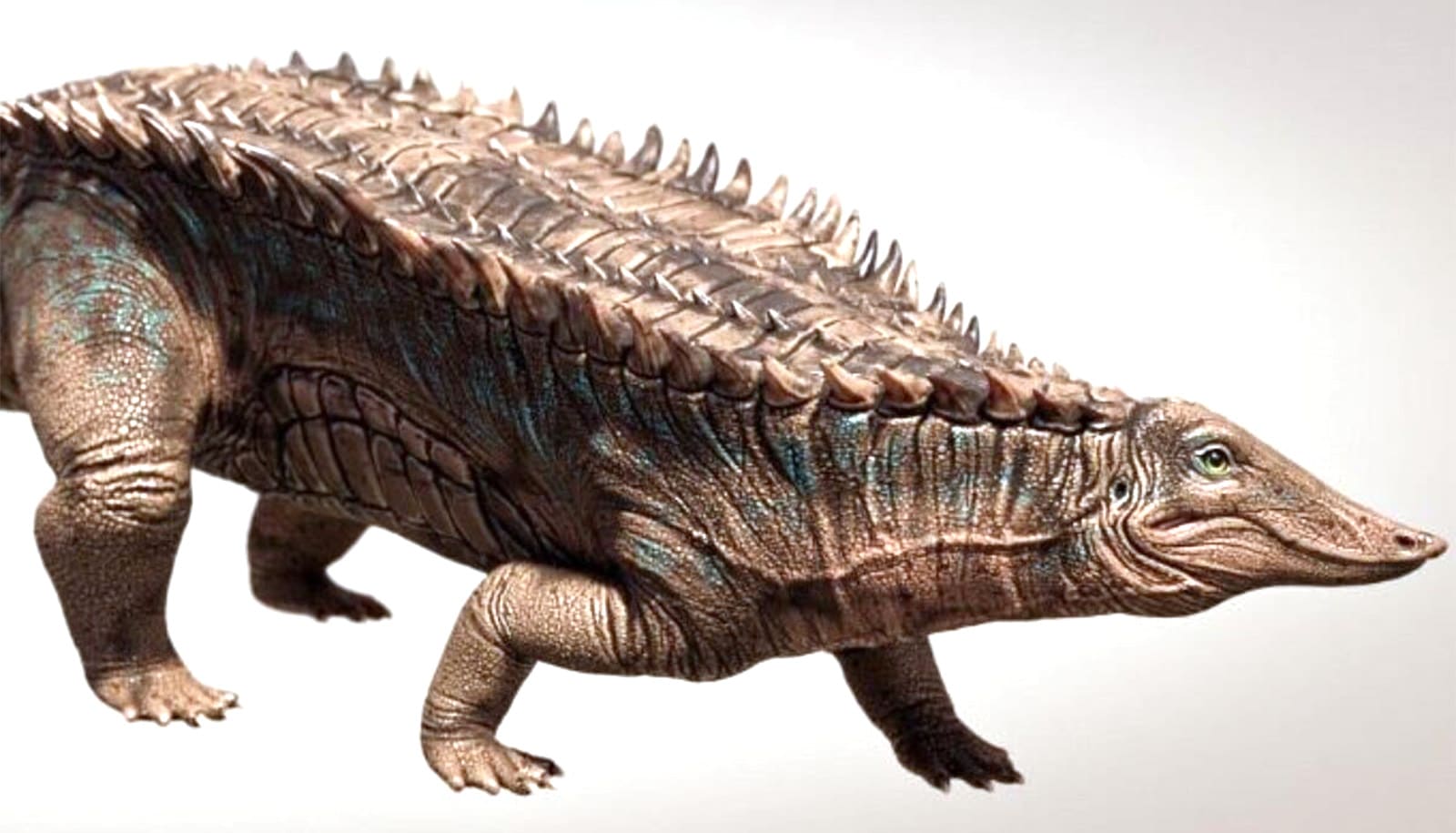

3D models of the American alligator skull will assist scientists who study extinct species, including dinosaurs, and other animals.

The skulls of alligators protect their brains, eyes, and sense organs while producing some of the most powerful bite forces in the animal kingdom. The ability to bite hard is critical for crocodilians to eat their food such as turtles, wildebeest, and other large prey.

“Collecting bite data from live animals like alligators can be pretty dangerous and potentially deadly, so accurate 3D models are the best way for biomechanists, veterinarians, and paleontologists interested in the function and evolution of these amazing animals to study them,” says Casey M. Holliday, associate professor of pathology and anatomical sciences in the University of Missouri School of Medicine.

“It is impossible to analyze the bite forces in extinct hard-biting species like the giant Cretaceous crocodile Deinosuchus, or the famous bone-crunching dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex, so precise models are imperative when studying extinct species,” he says.

Evolution hasn’t revamped alligators in 8 million years

The team’s approach was to first report naturalistic, three-dimensional computational modeling of the jaw muscles that produce forces within the alligator skulls to better understand how bite forces change during growth. Then, they compared their findings to previously reported bite forces collected from live alligators.

“Because alligators and crocodilians have had such extreme feeding performance for millions of years, they have been a popular topic of study for paleontologists and biologists,” says Kaleb Sellers, a doctoral student in Holliday’s lab.

“Our models stand out because we’re the first to distribute loads of their huge muscles across their attachment surfaces on the alligator skull. This lets us better understand how muscle forces and bite forces impact the skull,” Sellers says.

These new methods and findings pave the way to better understanding the 3D biomechanical environment, development, and evolution of the skull of not only alligators, but other crocodilians, birds, dinosaurs, and other vertebrates, Holliday says.

Alligator babysitters take chicks as ‘payment’

The researchers validated their simulations using previously reported bite-force data.

The study appears in the Journal of Experimental Biology. Additional coauthors on the study are from the University of Missouri and the University of Southern Indiana.

The University of Missouri Research Board, Missouri Research Council, the National Science Foundation, and the department of pathology and anatomical sciences supported the work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Source: University of Missouri