A new imaging technology could help surgeons removing breast cancer lumps confirm that they have cut out the entire tumor—reducing the need for additional surgeries.

About 300,000 new cases of invasive breast cancer are discovered annually. Of these, 60 to 75 percent of patients undergo breast-conserving surgery, also called lumpectomies. These surgeries attempt to remove the entire tumor while retaining as much of the undamaged breast tissue as possible. In contrast, a mastectomy removes the entire breast.

“…we could analyze the tumor right in the operating room, and know immediately whether more tissue needs to be removed.”

The extracted tissue then goes to a lab where it is separated into thin slices, stained with a dye to highlight key features, and analyzed. If tumor cells show up on the surface of the tissue sample, it indicates that the surgeon has cut through, not around, the tumor—meaning that a portion of the tumor remains and the patient will need follow-up surgery to have more tissue removed.

After a week or two waiting for lab results, 20 to 60 percent of patients find out that they need a second surgery to have more tissue removed. But, “what if we could get rid of the waiting?,” asks Lihong Wang, professor of medical engineering and electrical engineering at California Institute of Technology.

“With 3D photoacoustic microscopy, we could analyze the tumor right in the operating room, and know immediately whether more tissue needs to be removed.”

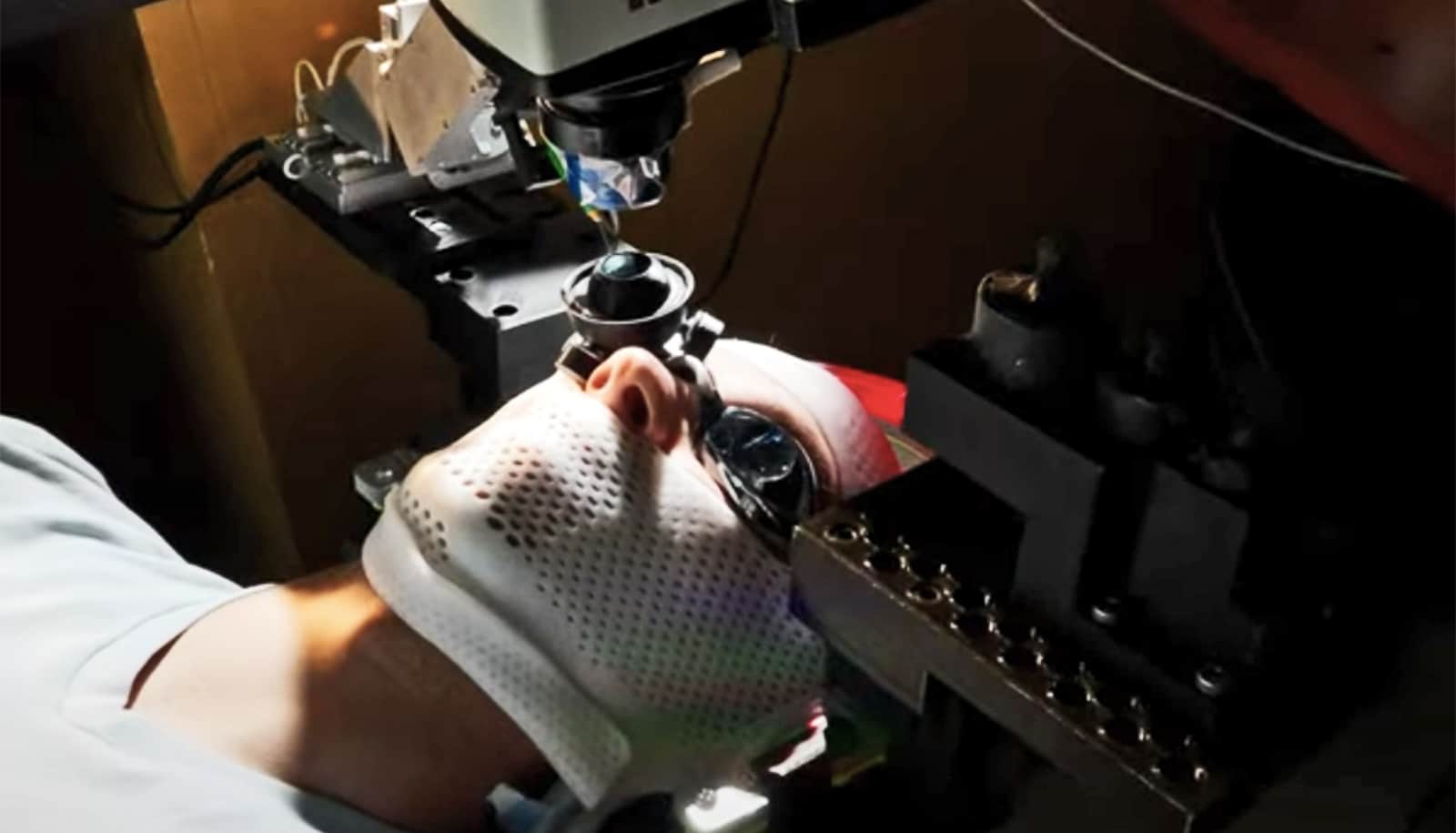

Wang’s lab invented 3D photoacoustic microscopy. PAM excites a tissue sample with a low-energy laser, which causes the tissue to vibrate. The system measures the ultrasonic waves emitted by the vibrating tissue. Because nuclei vibrate more strongly than surrounding material, PAM reveals the size of nuclei and the packing density of cells. Cancerous tissue tends to have larger nuclei and more densely packed cells.

As reported in the journal Science Advances, PAM produces images capable of highlighting cancerous features, with no slicing or staining required.

Surgery extends lives of women with Stage IV breast cancer

Although Wang’s team has focused primarily on breast cancer tumors, his work has potential applications for any analysis of excised tumors, like those with melanoma and pancreatic cancer. In a proof-of-concept scan described in the new paper, PAM analyzed a sample in about three hours. Comparable traditional microscopy takes about seven hours to achieve the same results.

Wang says the analysis time could be cut down to 10 minutes or less with the addition of faster laser pulse repetition and parallel imaging. This would make the technology useful for clinical applications.

“Because the device never directly touches a patient, there will be fewer regulatory hurdles to overcome before gaining FDA approval for use by surgeons,” Wang says. “Potentially, we could make this tool available to surgeons within several years.”

The National Institutes of Health and the Siteman Cancer Center funded the work. Wang conducted this research while his Optical Imaging Laboratory was located at Washington University in St. Louis. He moved the lab to Caltech in January 2017.

Source: Caltech