The 1918 influenza pandemic provides a cautionary tale for what the future may hold for COVID-19, says Siddharth Chandra.

After a decade studying a flu virus that killed approximately 15,000 Michigan residents, Chandra, a professor in the James Madison College at Michigan State University, saw his research come to life as he watched the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Bad things can still happen a year or two from now even if we see a decrease in the number of cases now.”

“It was so surreal,” says Chandra, who has a courtesy appointment in epidemiology and biostatistics. “All of a sudden, I was living my research.”

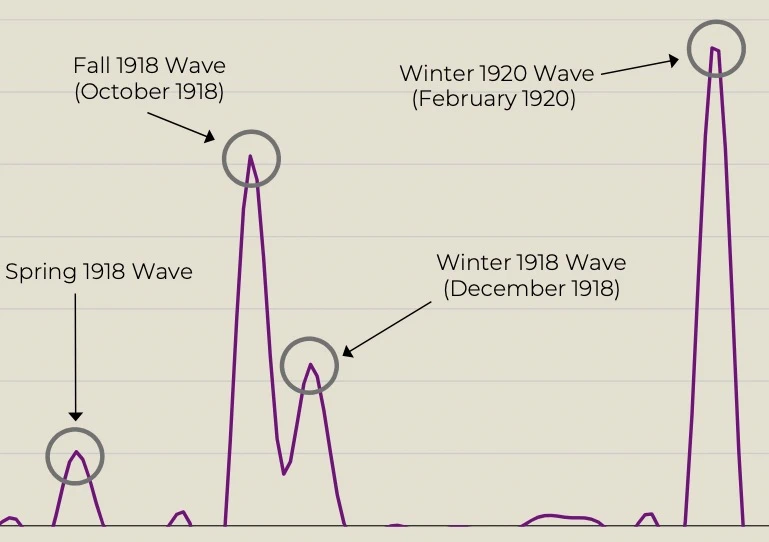

Using influenza infection and mortality data on Michigan from 1918-1920, Chandra identified four distinct waves. The first large peak was in March 1918. “After a second spike in cases in October 1918, the governor instituted a statewide ban on public gatherings,” Chandra says. “Much like the restrictions that were put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

After three weeks, the number of cases decreased and the ban was lifted, which led to another peak in December 1918. “The ban didn’t stop the spread of the flu. It just delayed the spike in cases,” he says.

Chandra mapped the data showing the peaks and spikes in cases from October 1918 and December 1918 and tracked flu virus case growth by county over time. In October, counties in the southern part of the state and near the Mackinac Straits had the highest numbers but by December, the highest numbers of cases were in the heart of the state.

The most surprising piece of data came 18 months later in February 1920, when a statewide explosion of cases created a massive spike even larger than the one in October 1918. For Chandra, it is an educated guess as to the reasons for this delayed increase.

“Assuming it’s the same influenza virus, World War I ended in 1918 and the men were coming home to their families,” he says. “We had a mobile agent that brought the virus home to infect family members, which would explain the increase in cases among children and the elderly.”

Unfortunately, there is not a way to confirm this, Chandra says. “We would need samples from patients in 1920 from across the state. Then, we would need to compare those with samples from patients in 1918 from across the state, and that’s not likely to happen.”

The weather may have also been a factor since cool temperatures with low humidity likely provided optimal conditions for the virus to live and spread. Another factor that played a role was the absence of a vaccine.

“In 1918, there was no hope for a vaccine. In 2021, we have a vaccine available,” he says.

One of the key insights from the 1918 pandemic that can inform the public health response to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is the number of people susceptible to the virus, Chandra says. Which means that it is possible that a spike like the February 1920 one will occur in late 2021 or early 2022.

“So many people will remain susceptible until they get vaccinated,” Chandra says. “Bad things can still happen a year or two from now even if we see a decrease in the number of cases now. We still have over 200 million people walking around who are susceptible to the virus, including myself.”

The study appears in the American Journal of Public Health. Additional coauthors are from James Madison College and Michigan State University.

Source: Michigan State University