Since the 2005 European Union ban on bird imports, trade of wild birds has dropped about 90 percent globally, a new study suggests.

The study demonstrates how the EU’s ban decreased the number of birds traded annually from about 1.3 million to 130,000. International trade of wild birds is a root cause of exotic birds spreading worldwide.

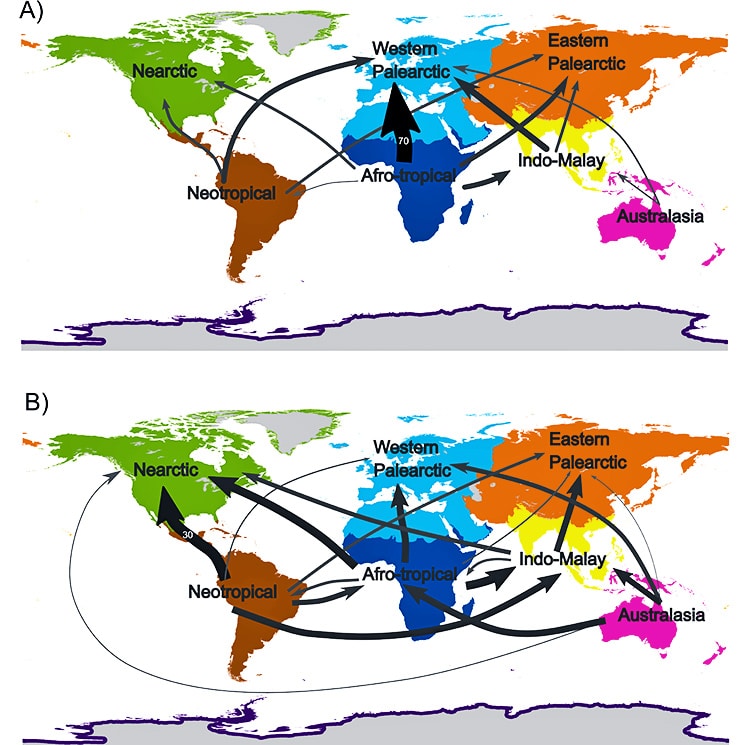

Birds are the most traded animals in the world and, historically, Europe has been the main importer of wild birds globally. Before 2005, when the EU banned trade of wild birds, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain accounted for the import of two thirds of all wild birds sold on the global market. The birds mainly came from West Africa, with 70 percent of bird exports coming from Guinea, Mali, and Senegal.

“When wild birds are caught and sold to another country it has consequences in both areas. In the country the birds are captured, it can lead to biodiversity loss,” says Diederik Strubbe of the Center for Macroecology, Evolution, and Climate at the University of Copenhagen.

“Likewise, our study shows that international bird trade is a main cause of exotic birds spreading around the world. The birds can damage local ecosystems, destroy crops, and outcompete local birds. The EU trade ban, and the following dramatic drop in the number of traded birds, has strongly reduced this risk across most of the globe,” Strubbe says.

Before 2005, almost all wild bird exports came from two groups of birds. Passerines, which include popular pet birds like the yellow-fronted canary and the common waxbill, made up almost 80 percent of bird exports while parrots accounted for about 18%.

After the EU trade ban, things changed. Today, passerine birds constitute less than 20 percent while parrots have increased to almost 80 percent of all traded birds. Parrots are the most threatened group of bird species, and the bird most likely to establish in countries it not naturally occurs.

5 big threats in the fight against invasive species

Latin America overtook West Africa’s as the main exporter of wild birds, and the continent is now responsible for more than 50 percent of global wild bird exports. Countries such as Mexico and the US became important new buyers on the market, with imports increasing from about 23,000 to 82,000 birds annually.

“Worryingly, we document a shift in wild bird trade towards areas with a high biodiversity. For example, several south-east Asian nations have emerged as important bird importers. These regions are now exposed to a higher risk of bird invasions,” says Luis Rein of the CIBIO-InBIO Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources at the University of Porto.

“Thus, our results clearly speak for a global wildlife trade ban, if we want to reduce the number of traded birds, and minimize the risk of exotic birds spreading. The positive thing is that our study shows such a policy will likely be effective,” Rein says.

Imported pet salamanders carry killer fungus

Researchers report their findings in the journal Science Advances.

The study is based on data from CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

Source: University of Copenhagen