Scientists have developed a nanoparticle that can deliver chemotherapy to tumor cells that have spread to bone.

Spreading breast cancer often infiltrates bone, causing fractures and intense pain. In such cases, chemotherapy is ineffective because the environment of the bone protects the tumor, even as the drug has toxic side effects elsewhere in the body.

In mice implanted with human breast cancer and exposed to circulating cancer cells likely to take up residence in bone, the researchers used the treatment to kill tumor cells and reduce bone destruction while sparing healthy cells from side effects.

“For women with breast cancer that has spread, 70 percent of those patients develop metastasis to the bone,” says senior author Katherine N. Weilbaecher, a professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. “Bone metastases destroy the bone, causing fractures and pain. If the tumors reach the spine, it can cause paralysis. There is no cure once breast cancer reaches the bone, so there is a tremendous need to develop new therapies for these patients.”

In the study, the researchers show that breast cancer cells that spread to bone carry molecules on their surface that are a bit like Velcro, helping tumor cells stick to the bone. These adhesion molecules also sit on the surface of cells responsible for bone remodeling, called osteoclasts.

“In healthy bones, osteoclasts chew away old, worn out bone, and osteoblasts come in and build new bone,” says Weilbaecher, who treats patients at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine. “But in cancer that spreads to bone, tumors take over osteoclasts and essentially dig holes in the bone to make more room for the tumor to grow.”

“When we gave these nanoparticles to mice that had metastases, the treatment dramatically reduced the bone tumors…”

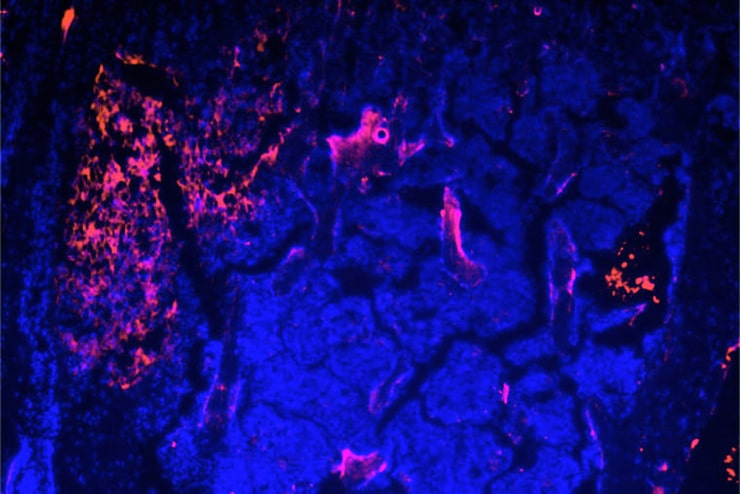

Weilbaecher says she and her colleagues were surprised to find that the same adhesive molecule on the surface of osteoclasts also is present in high levels on the surface of the breast tumors that spread to bone. The research showed that the molecule—called integrin αvβ3—was absent from the surfaces of the original breast tumor and from tumors that spread to other organs, including the liver and the lung. The researchers confirmed that this pattern also was true in biopsies of human breast tumors that had spread to different organs.

A collaboration with co-senior author Gregory M. Lanza, a professor of medicine and of biomedical engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, then led to the design of a nanoparticle that combines the bone-adhesion molecules with a form of the cancer drug docetaxel, which can treat breast cancer as well as other tumors.

The adhesive molecules allow the nanoparticle to penetrate the otherwise protective environment of the bone matrix in a way that, in essence, mimics the spreading of the tumor cells themselves. The resulting delivery method can keep the chemotherapy drug contained in the nanoparticle until the adhesion molecules make contact with the tumor cell, fusing the nanoparticle with the cell surface and releasing the drug directly into the cancer cell.

“When we gave these nanoparticles to mice that had metastases, the treatment dramatically reduced the bone tumors,” Weilbaecher says. “There was less bone destruction, fewer fractures, less tumor. The straight chemo didn’t work very well, even at much higher doses, and it caused problems with liver function and other toxic side effects, which is our experience with patients.

“But if we can deliver the chemo directly into the tumor cells with these nanoparticles that are using the same adhesive molecules that the cancer cell uses, then we are killing the tumor and sparing healthy cells.”

Lots of breast cancer patients suffer from ‘chemo-brain’

The study appears in the journal Cancer Research.

Grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH); the St. Louis Men’s Group Against Cancer; Siteman Cancer Center; the Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging, supported by Washington University School of Medicine, grants from the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital; a grant from the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke; and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital provided funding for the research.

A Washington University Musculoskeletal Research Center grant; a Hope Center Alafi Neuroimaging Lab shared instrumentation grant; a Molecular Imaging Center at Washington University grant; and the St. Louis Breast Tissue Registry (funded by the surgery department at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis) provided technical support.