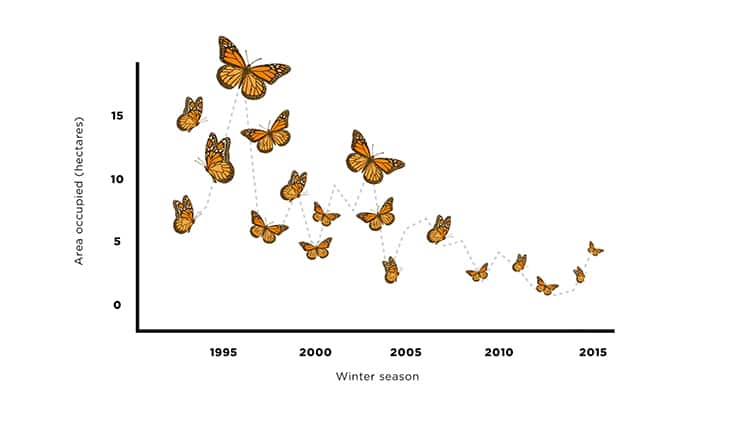

A wide variety of factors, including herbicide use, climate change, and habitat loss, have caused the decline of monarch butterflies in North America, a new study shows.

“We need to think of migratory species at regional scales to truly understand how changes in climate and land use affect population trends,” says Elise Zipkin, a integrative biologist from Michigan State University and a coauthor of the study in the journal Ecography.

“Global declines in migratory species, including monarchs, suggest that broad-scale conservation action may be necessary to prevent the loss of migratory populations.”

In that vein, the research team incorporated features from the butterflies’ complex continental movements to study the factors influencing summer populations in Illinois using data from a long-term citizen science monitoring program.

Unlike other migratory species, which have distinct summer and winter grounds, monarchs take multiple generations to travel from Mexico to Texas, from Texas to the Midwest, from the Midwest and into Canada, and finally, back from the upper Midwest and Canada to Mexico.

Thus, the numbers of butterflies in small fields in the Midwest are linked to events that happen across the continent, says Sarah Saunders, integrative biologist and lead author.

“The connection between population dynamics from winter to spring to summer is more complex than in other species,” she says. “Our study provides the first empirical evidence of a negative association between glyphosate application and local abundance of adult monarch butterflies during 1994-2003, the initial phase of large-scale herbicide adoption in the Midwest.”

Glyphosate, a key ingredient found in Roundup and other herbicides, may be a contributing cause of population decline due to its ability to reduce milkweed plants. While milkweed serves as the host plant for monarch eggs, the extent in which milkweed loss affects monarch trends is still controversial, she adds.

Milkweed might not be the trouble for monarchs

Along with the impacts of herbicides, the study examined the effect of surrounding crop cover in summer habitat as well as cross-seasonal effects of spring weather fluctuations in Texas and population changes on the wintering grounds in Mexico.

“Butterflies face myriad challenges, and habitat loss and climate change are clearly important pieces of it,” Zipkin says. “Our long-term goal is to examine the many stressors on monarchs across all seasons and identify which ones are the most critical. Future research could then offer solutions on how to develop effective conservation strategies.”

The team’s research could generate answers that eventually help reverse the nearly 20-year decline of monarch butterflies observed in Mexico. It gives hope to anyone, scientists and the public alike, who has ever witnessed the mass of overwintering butterflies in Mexico or cheered a flitting monarch as it traverses vast distances across the United States.

How monarchs make it to Mexico without a map

“Migration—whether it’s undertaken by the smallest insects or the largest mammals—is a captivating phenomenon,” Saunders says. “We hope that our study sheds light on how events and conditions during different stages affect the monarch butterfly’s annual cycle as well as provides findings that can inform future conservation efforts.”

Additional scientists contributing to this study are from Georgetown University, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, and USGS Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center.

Source: Michigan State University