The widespread adoption of mindfulness and meditation as a means to mental and physical wellness has been rapid in recent years, but dependable scientific evidence has lagged behind.

A new paper in Perspectives on Psychological Science offers a “critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda” to help the burgeoning mindfulness industry replace ambiguous hype with rigor in its research and clinical implementations.

“We are sometimes overselling the benefits of mindfulness to pretty much any person who has any condition…”

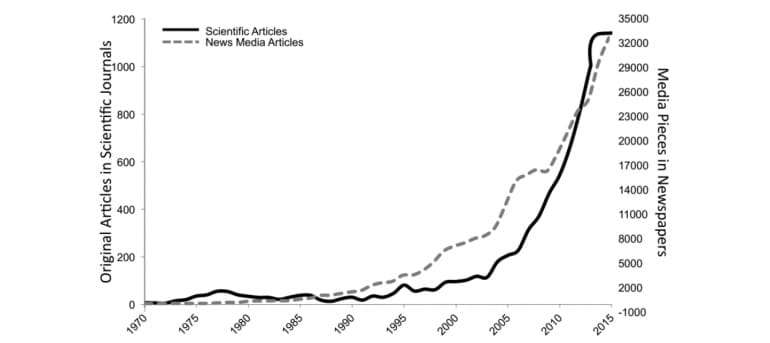

Recent years have seen a huge surge not only in media and scientific articles about mindfulness and meditation, but also in the implementation of medical interventions for everything from depression, addiction, pain, and stress. The widespread adoption of therapies has put the field at a critical crossroads, where appropriate checks and balances must be implemented, the authors argue.

“Misinformation and poor methodology associated with past studies of mindfulness may lead public consumers to be harmed, misled, and disappointed.”

Adverse effects

“We are sometimes overselling the benefits of mindfulness to pretty much any person who has any condition, without much caution, nuance, or condition-specific modifications, instructor training criteria, and basic science around mechanism of action,” says coauthor Willoughby Britton, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavior at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

“The possibility of unsafe or adverse effects has been largely ignored. This situation is not unique to mindfulness, but because of mindfulness’s widespread use in mental health, schools, and apps, it is not ideal from a public health perspective.”

The point of the article is not to disparage mindfulness and meditation practice or research, but to ensure that their applications for enhancing mental and physical health become more reflective of scientific evidence, says lead author Nicholas Van Dam, a clinical psychologist and research fellow in psychological sciences at the University of Melbourne.

“…these practices might help people. But the rigor that should go along with developing and applying them just isn’t there yet.”

So far, such applications have largely been unsupported, according to major reviews of available evidence in 2007 and 2014.

“The authors think there can be something beneficial about mindfulness and meditation,” Van Dam says. “We think these practices might help people. But the rigor that should go along with developing and applying them just isn’t there yet. Results from the few large-scale studies that have been conducted so far have proven equivocal at best.”

“Sometimes, truly promising fields of endeavor get outstripped by efforts to harvest them before they’re really ripe; then workers there must step back, pause to take stock, and get a better plan before moving onward,” adds coauthor David E. Meyer, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan.

Poorly defined

Among the biggest problems facing the field is that mindfulness is poorly and inconsistently defined both in popular media and the scientific literature. There “is neither one universally accepted technical definition of ‘mindfulness’ nor any broad agreement about detailed aspects of the underlying concept to which it refers.” As a result, research papers vary widely in what they actually examine, and often, their focus can be hard to discern.

“Any study that uses the term ‘mindfulness’ must be scrutinized carefully, ascertaining exactly what type of ‘mindfulness’ was involved, what sorts of explicit instruction were actually given to participants for directing practice,” the authors write. “When formal meditation was used in a study, one ought to consider whether a specifically defined type of mindfulness or other meditation was the target practice.”

“Without specific, well-defined terms to describe not only practices but also their effects, studies of interventions such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) cannot provide valid and comparable measurements to produce reliable evidence.”

As part of its proposed remedy, the article offers a “non-exhaustive list of defining features for characterizing contemplative and medication practices.”

Along with specific, precise and standardized definitions, similar improvements in research methodology are also necessary. “Many intervention studies lack or have inactive control groups,” Van Dam says.

The field also has struggled to achieve consistency in what it is being measured and how to measure those things perceived to be of greatest importance to mindfulness.

The situation is akin to earlier psychological research on intelligence, Van Dam says. This concept proved to be too broad and too vague to measure directly. Ultimately, however, psychologists have made progress by studying the “particular cognitive capacities that, in combination, may make people functionally more or less intelligent.”

The authors recommend that “future research on mindfulness aim to produce a body of work for describing and explaining what biological, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and social, as well as other such mental and physical functions, change with mindfulness training.”

A wide variety of contemplative practices have been studied for an even larger variety of purposes, yet in both basic and clinical studies of mindfulness and meditation, researchers have rarely advanced to the stage where they can confidently conclude whether particular effects or specific benefits resulted directly from the practice.

Measured by the National Institutes of Health’s stage model for clinical research, only 30 percent of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have moved past the first stage, and only 9 percent have tested efficacy in a research clinic against an active control.

“Given the absence of scientific rigor in much clinical mindfulness research, evidence for use of MBIs in clinical contexts should be considered preliminary,” the authors write.

‘Calming’ meditation can feel super stressful

“Replication of earlier studies with appropriately randomized designs and proper active control groups will be absolutely critical. In conducting this work, we recommend that researchers provide explicit detail of mindfulness measures, primary outcome measures, mindfulness/meditation practices and intervention protocol.”

Researchers and care providers involved with delivering MBIs have begun to become more vigilant about possible adverse effects, but more needs to be done. As of 2015, fewer than 25 percent of meditation trials actively monitored for negative or challenging experiences.

Problems with MRI studies

Recent efforts to assess the neural correlates of mindfulness and meditation with technologies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetoencephalography, may perhaps have the potential to bring new rigor to the field. But these technologies so far have not fulfilled this potential.

Technologies such as MRI depend on subjects remaining physically still while being tested, and image quality can be affected by subjects’ rate of breathing. Experienced meditators may be better suited to maintaining ideal physiological states for MRI studies than are inexperienced individuals or non-meditators. Due to such problematic factors, between-group differences in brain scans might have little to do with the mental state researchers are attempting to measure and much to do with head motion and/or breathing differences.

Meditation calms, even if you’re not mindful

“Contemplative neuroscience has often led to overly simplistic interpretations of nuanced neurocognitive and affective phenomena,” the authors write. “As a result of such oversimplifications, meditative benefits may be exaggerated and undue societal urgency to undertake mindfulness practices may be encouraged.”

That’s the ultimate concern, the authors write. Insufficient research may mislead people to think that the vague brands of “mindfulness” and “meditation” are broad-based panaceas when in fact refined interventions may only be helpful for particular people in specific circumstances.

More, and much better, scientific studies are needed. Otherwise people may waste time and money, or worse, suffer needless adverse effects.

Source: Brown University