A new study suggests that fact-checking has little influence on what online news media covers, and fact-checks of false news stories spreading online—”fake news”—may use up resources newsrooms could better use covering substantive stories.

“Faculty and students have been agonizing recently about the emergence of fake news—false information packaged to deceive the public into thinking it was produced by professionals with respect for truth,” notes Thomas Fiedler, dean of the Boston University College of Communication, in his spring 2017 COMtalk column.

Another interested consumer of news—Barack Obama—described the new media landscape to New Yorker editor David Remnick last year: “Everything is true and nothing is true. An explanation of climate change from a Nobel Prize-winning physicist looks exactly the same on your Facebook page as the denial of climate change by somebody on the Koch brothers’ payroll.”

And fake stories, like cockroaches, tend to keep coming back. As Jim Rutenberg put it in his New York Times “Mediator” column: “Fake news dies hard.”

What to do about it: educate the public, convene scholars and journalists, set out to systematically identify and refute fake news? Those questions are the talk of campuses, think tanks, and newsrooms around the globe.

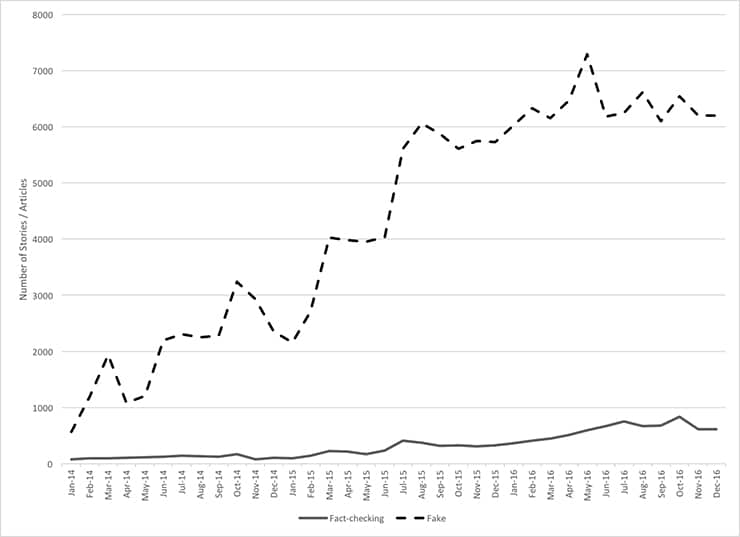

Two communications professors are doing their part to find the answers. Michelle Amazeen, an assistant professor of mass communication, advertising, and public relations, and Lei Guo, an assistant professor of emerging media studies, have analyzed three years of data on fake news and come up with some surprising findings, which appear in New Media & Society.

Their study, which uses computational modeling to examine the relationship between fake news and online news media, investigated the impact on online news media of seven fact-checking sites, PolitiFact.com, FactCheck.org, Snopes, Climate Feedback, Gossip Cop, Health News Review, and Wafflesatnoon.com.

Amazeen and Guo say more research is needed, and they caution that while their study measured the extent that fake news dictates part of the agenda for online media, it did not attempt to separate the chaff (fake news stories that went unquestioned and got repeated and circulated) from the wheat (stories that tested or refuted the fakery).

Their point: taken together, all those stories tied up a remarkable amount of news media resources that could have been devoted to other important issues.

Amazeen and Guo answer questions about their research and their thoughts on what journalists—and readers—can do to fight fake news:

What were the three biggest findings of your study?

Amazeen: The three biggest findings were: a) fake news stories do influence what online news organizations report, b) in particular, online partisan media have a reciprocal relationship with fake news—that is, they influence what fake news purveyors write about, and in turn, are then influenced by these fake news stories, and c) fact-checkers are not influential in the reporting of online news media.

I understand from your study that you weren’t able to determine if online news media were repeating fake news—or refuting fake news.

Amazeen: Yes, we cannot tell from our study whether the similarity in news reporting is based upon repetition of the fake news stories or refutation.

What surprised you the most about your findings?

Amazeen: I was surprised by how little influence fact-checkers have on the online media news agenda. It seemed like there was more attention than ever to fact-checking during the 2016 election. However, mentioning fact-checking in passing and using it to consistently frame how a news organization reports on an issue are evidently two different things.

I should acknowledge that our study is limited by the sample of seven fact-checking organizations we were able to include given our data collection methods. Although we were not able to include the Washington Post’s Fact Checker or localized fact-checkers in our sample, we did include two of the largest national fact-checkers: FactCheck.org and PolitiFact.com (and its state partners).

Guo: Fact-checkers appeared to be largely autonomous. Their decision on what issues to cover did not appear to be dictated by, or to influence, fake news or any other type of news.

The study found that serious journalistic efforts to test or debunk fake news use up resources that could be devoted to other stories—e.g., policy issues in a presidential campaign. What’s your takeaway? Should media outlets devote less or more time and resources to debunking fake news?

Amazeen: Our study found that given the tremendous increase in the number of fake news stories over the last three years, the media would be negligent to ignore the phenomenon. Research has been inconsistent on whether repeating inaccurate information (even when fact-checking) is beneficial. Some studies have shown that correcting mis/disinformation can be ineffective or even backfire.

Can you give an example of how correcting misinformation might backfire?

Amazeen: Research has shown that under certain circumstances, refuting connections between vaccinations and autism can backfire by increasing belief in the side effects of vaccinations rather than decreasing it.

However, other research has shown that corrections that repeat misinformation are more effective. For instance, as in the case of breaking news, first accounts may contain some inaccuracies. If a story about a wildfire inaccurately states that it was deliberately set, rather than ignoring initial reports or vaguely indicating that initial reports were inaccurate, research suggests it will be more effective for readers to understand that although initial reports indicated the fire was deliberately set, authorities concluded that the fire was ignited by a lightning strike.

I think part of what news organizations need to be doing beyond the correction of fake stories is helping people become more news literate. That is, help people to understand how and why fake news is proliferating. This may help to inoculate them from future fake news attacks.

Guo: We found some media (e.g., partisan media) always covered what fake news decided to cover (no matter how they covered). We argued that these media could have devoted the resources they used to cover fake news to other more important issues. We believe no matter how media cover the fake news, they do drive people’s attention to the fake news, therefore in some way helping distribute the fake news.

Psychologically speaking, people’s attention is limited. If they are considering all kinds of fake news, they will not have time to consider other more important issues. In this light, news media might want to devote less time and resources to covering news about fake news.

Can you offer any guidance for news consumers or journalists who want to combat fake news?

Amazeen: Journalists need to be adopting the “ongoing story structure.” That’s a term used by Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania and cofounder of FactCheck.org, and what it means is that instead of correcting a fake news story once and moving on, newsrooms need to be monitoring and reporting on the continued prevalence of particular stories.

I have seen a pivot in this direction by some newsrooms recently, tracing the origins of particular fake news stories and charting where it spreads. Craig Silverman of BuzzFeed News has been doing an extraordinary job leading this charge.

News consumers should be mindful of the source of news stories. With the prevalence of social media, news stories often become unmoored from their source—it can be hard to tell where an article came from. And with the spread of covert marketing practices, it can also be hard to tell a news article from online advertising that’s imitating a news article. That undermines a news organization’s ability to credibly fight the fake news battle. Bottom line: news audiences must be aware of what they are consuming—is it legitimate news, fake news, or advertising?

Guo: This is a hard question. Maybe news media should cover less news about fake news. If news consumers are not sure about a claim, they can go to credible/professional fact-checking websites for more information.

But our results showed that fact-checkers did not follow other news media, including fake news websites, for issues of coverage. So I think they might want to spend more time fact-checking news covered by certain media (e.g., partisan media), not just claims made by politicians.

<em>Source: <a href=”http://www.bu.edu/research/articles/fake-news-influences-real-news/” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener noreferrer”>Boston University</a></em>