Scientists have created a new method for producing “bio oil” from trees killed by the mountain pine beetle. The new method is more cost-effective than previous methods, potentially making way for commercial fuel applications, a new study suggests.

The mountain pine beetle has destroyed more than 40 million acres of forest in the western United States. That amounts to an area the size of Washington state that is strewn with conifers left for dead.

The beetles introduce a fungus that prevents critical nutrients and water from traveling within a tree. Beetles also lay their eggs under the bark and the feeding larvae help kill the trees, sometimes within several weeks of the initial attack.

These standing dead trees can fall at any moment or add fuel to a wildfire, and scientists and land managers are left scrambling to deal with millions of the precarious dead giants. Harvesting the wood for lumber is out of the question, because the infestation stains the wood and causes the tree to crack on the inside.

Now, researchers have made new headway on a solution to remove beetle-killed trees from the forest and use them to make renewable transportation fuels or high-value chemicals. The researchers have refined this technique to process larger pieces of wood than ever before—saving time and money in future commercial applications. They published their methods in the journal Fuel.

“We came up with a different way of converting wood into oil—that’s really the main accomplishment of this project,” says senior author Fernando Resende, a Univeristy of Washington assistant professor of bioresource science and engineering in the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences.

“Not only do we want to reduce the costs, but we are hoping to increase the value of what we produce so we have a better chance of making it commercial.”

The process of heating wood and other natural materials at extreme temperatures to create oil—called “fast pyrolysis”—is being widely explored in research labs across the country. Each system varies, but the general process involves heating small pieces of organic material in an oxygen-free chamber at about 500 degrees Celsius, until the solid material becomes a vapor.

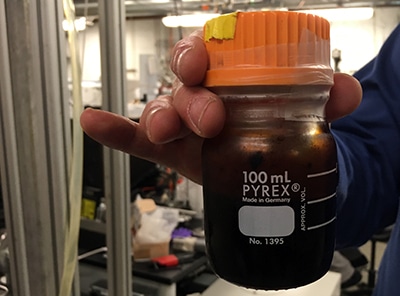

As the vapor rises and moves into other chambers, it cools and becomes a dark brown liquid fuel. Scientists call this “bio oil,” and it is already used in some European countries for heating hospitals.

Poplar trees engineered to break down into biofuel

Researchers, including the team looking at beetle-killed trees in Washington, currently are testing whether this bio oil can be upgraded by adding substances called catalysts. This upgrade intends to convert the bio oil into transportation fuels that resemble gasoline and diesel.

The beetle-killed trees are a good fit for making bio oil, Resende says, in part because the entirety of a tree becomes extremely dry when it is killed by an infestation. That makes for a simpler fast-pyrolysis process, because it isn’t necessary to first dry the wood before heating it to extreme temperatures.

“If you can extract the wood and process it using fast pyrolysis, not only will you free up space and safety hazards in the forest, but you also have the organic liquid that could potentially be used for products,” Resende says.

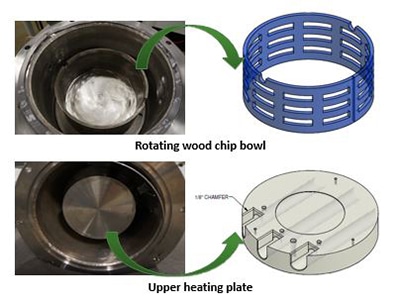

The system can efficiently break down woodchip-sized pieces, though the team has successfully turned an entire log into bio oil. Other fast pyrolysis systems must use small wood pellets 1 to 2 millimeters in length, which often adds an extra step of grinding larger pieces down to the appropriate size before converting them to bio oil.

How to make biofuel ‘wood chippers’ work faster

In the new method, woodchips are placed on a rotating surface and a hot stainless steel plate moves down from above, crushing the wood. The woodchips become hot from direct contact with the metallic surface, and the chemical transformation from solid to vapor begins.

The researchers say this method could be used in mobile pyrolysis units so dead trees can be processed on site, saving on transportation costs associated with moving large pieces of wood out of the forest. The mobile units—cylinder-shaped reactors that sit on a small flatbed truck—are already being used for standard wood-to-oil processing, and the improvements by the team could make the process more efficient and cost effective, they say.

The National Institute of Food and Agriculture and University of Washington’s School of Environmental and Forest Sciences funded the work.

Source: University of Washington