The answer to why there aren’t any animals with three legs may be at the core of animal evolution, a new essay argues.

Tracy Thomson, graduate student in the earth and planetary sciences department at the University of California, Davis, has been pondering the non-existence of tripeds. He recently published an essay on the topic in Bioessays.

Thomson got the idea after taking a graduate class on evolution with paleontologist Geerat Vermeij, who challenged the students to come up with a “forbidden phenotype:” an animal or plant that does not and cannot exist.

“If we’re trying to understand evolution as a process we need to understand what it can and can’t do.”

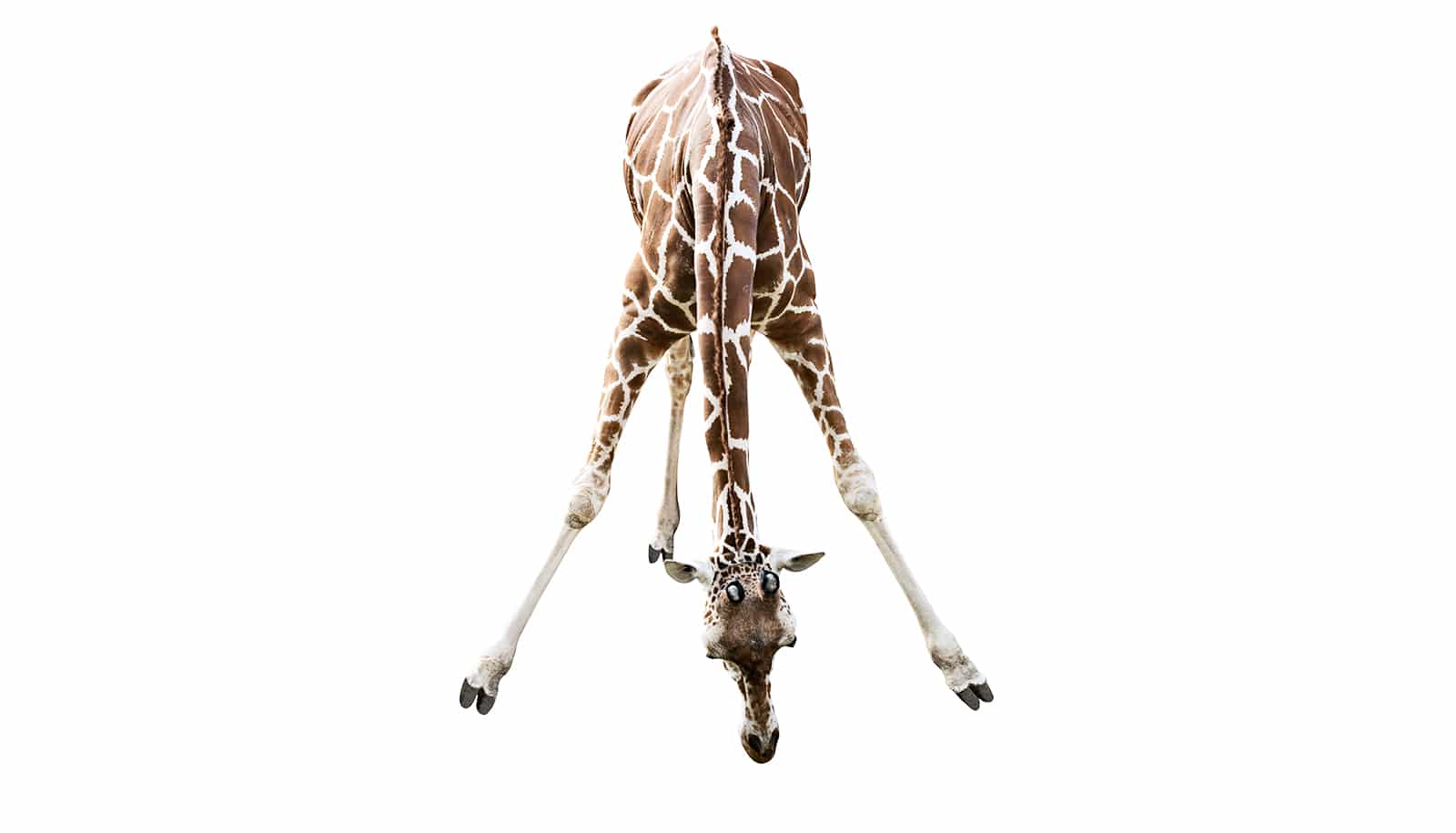

Thomson points out that there are lots of animals that use a tripod stance to rest. Meerkats in an upright stance rest on their tail and rear feet; woodpeckers use tail feathers to brace themselves against a tree-trunk.

A tripod stance does not require any energy to be stable, Thomson notes. Unlike, for example, standing upright on two feet, which does require some muscle work as well as relatively large feet.

Three-limbed movement is less common. Insects, which have six legs, have a mode of movement where their legs move in sets of three: two legs on one side and one on the opposite side are on the ground, with the opposite legs moving, at any time. This is called the “alternating tripod” gait.

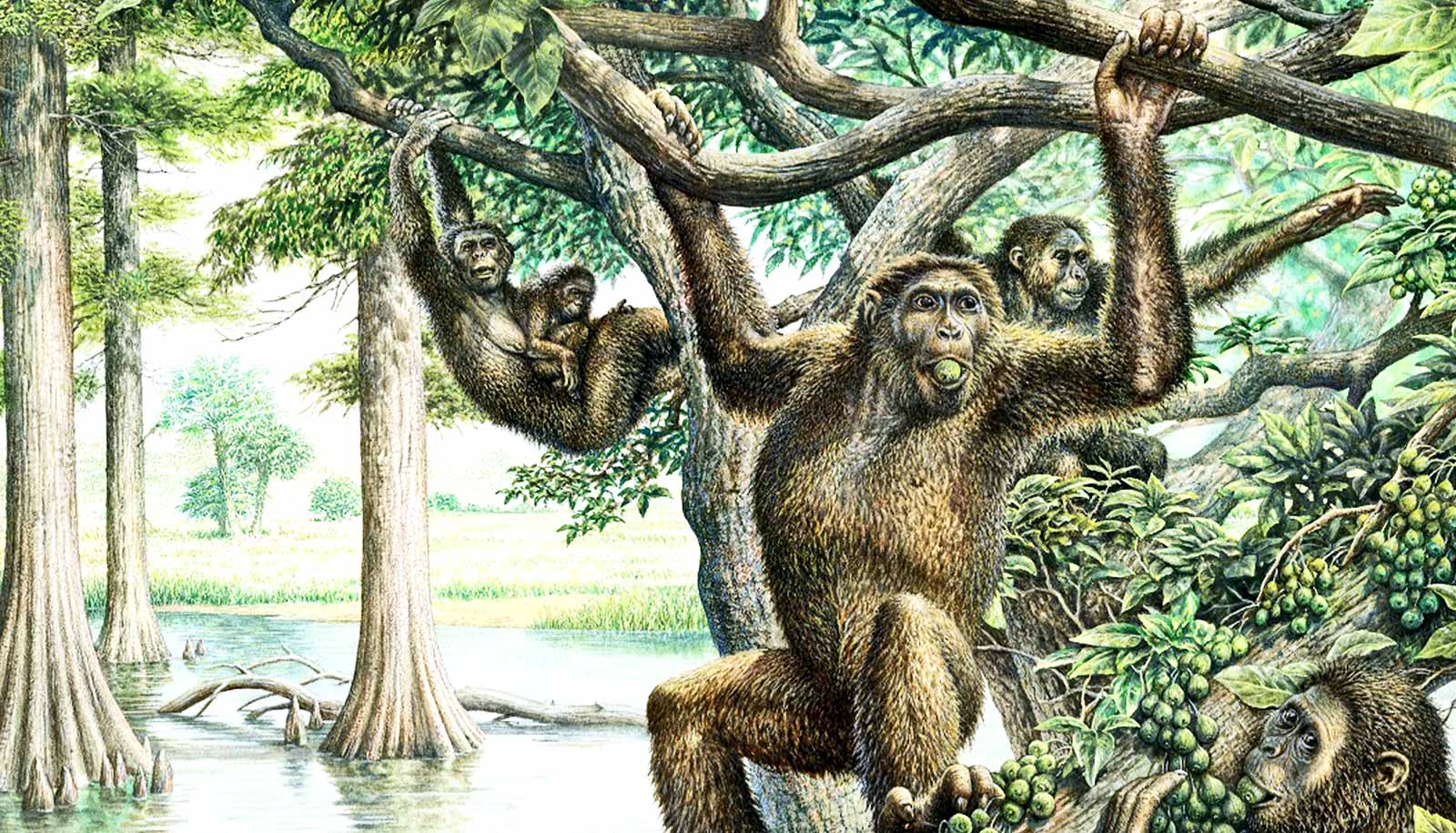

Many tree-dwelling animals use their tails for additional gripping, although they may be moving with all four of their limbs as well. Parrots are quite tripedal, using their strong, flexible beak as an additional grip to maneuver in tree branches.

Long rear feet make it difficult for kangaroos to “walk” like other mammals. Instead, they use their strong tail and front limbs to push the rear feet off the ground and forwards while grazing.

Given that three-limbed movement does seems to work for some animals, why are there no animals with three legs? That might go back a long, long way, Thomson says.

“Almost all animals are bilateral,” he says. The code for having two sides to everything seems to have got embedded in our DNA very early in the evolution of life—perhaps before appendages like legs, fins, or flippers even evolved. Once that trait for bilateral symmetry was baked in, it was hard to change.

With our built-in bias to two-handedness, it can be hard to figure out how a truly three-legged animal would work—although that has not stopped science fiction writers from imagining them. Perhaps trilateral life has evolved on Enceladus or Alpha Centauri or Mars and has as much difficulty thinking about two-limbed locomotion as we do thinking about three.

This kind of thought experiment is useful for developing our ideas about evolution, Thomson says.

“If we’re trying to understand evolution as a process we need to understand what it can and can’t do,” he says.

Source: UC Davis